Exploring the geography of Greek toponyms

Aside from its millenary history, rich culture and friendly inhabitants, Greece offers a plethora of interesting topics to research to both native and foreigners. Full of mountains and scattered islands, its diverse geography contains a myriad of toponyms that hides curious stories and patterns. In this article, we will have a look at them using data analysis techniques.

The base for this study is the Hellas DB, which collects information about Greek towns and other locations, as well as coordinates for most of them, based on official data from the Hellenic Statistical Service. To perform the calculations, monasteries and uninhabited islets have been removed from the table.

A quick introduction to Greece’s administrative division

Before diving into the data, we need to have a basic knowledge of Greece’s administrative divisions. The country is divided into 13 perifereies or regions, which contain 75 regional units or provinces. These regional units further divide into 332 municipalities. Since this affects the analysis, it is worth noting that Athens is divided in four regional units and that Mount Athos constitutes a self-governing special entity. Bearing this in mind, we’re ready to go straight to the matter!

Unique and repeated toponyms

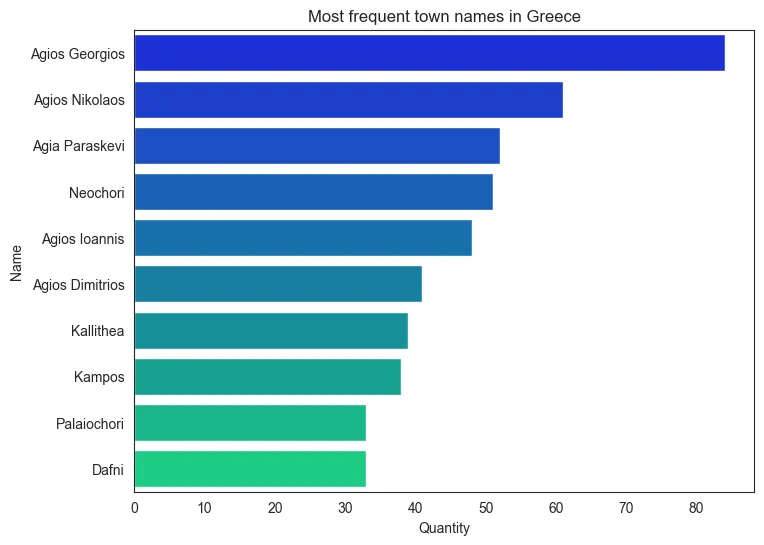

In this database, 12 904 settlements are included. However, there are only 9 015 different location names. It turns out that 40 % of the locations share its toponym with at least one more location, and often more than one. Besides, the 50 most common names make up 9 % of all Greek toponyms. This constitutes a good starting point to analyze the frequency of toponyms in Greece.

As shown in the table above, the locations names after saints tend to be very frequent. In total, 670 locations start by “Agios” or its derivatives, which equals almost 1 out of every 20 locations (4,72 %). There are five provinces in which more than 10 % of the locations are named after saints: Mykonos (14,3 %), Magnisia (12,7 %), Boeothia (11,7 %) and Limnos (11,3 %). In contrast, Thasos, Evros and Kalymnos are the only provinces without a single town named Agios.

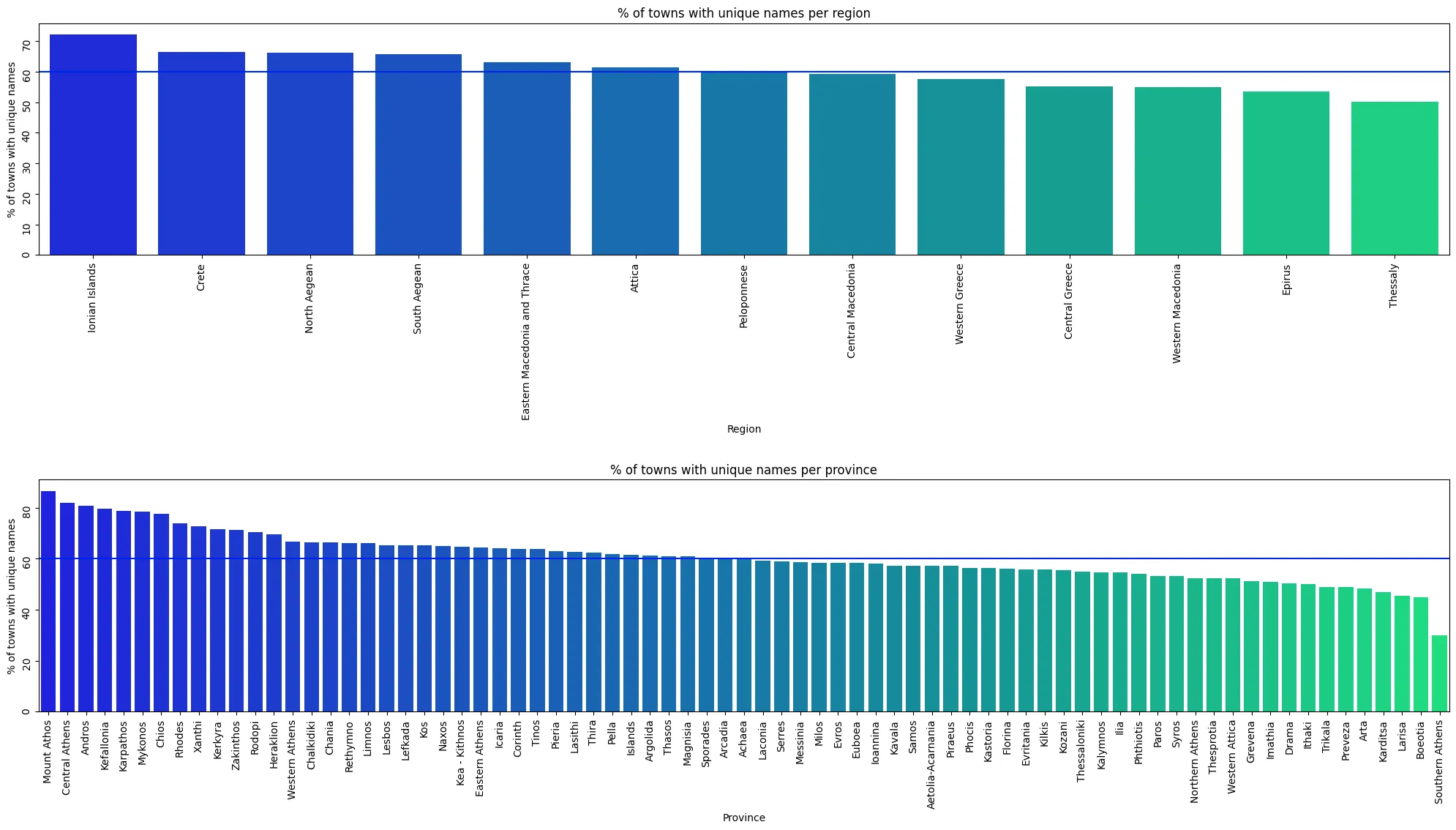

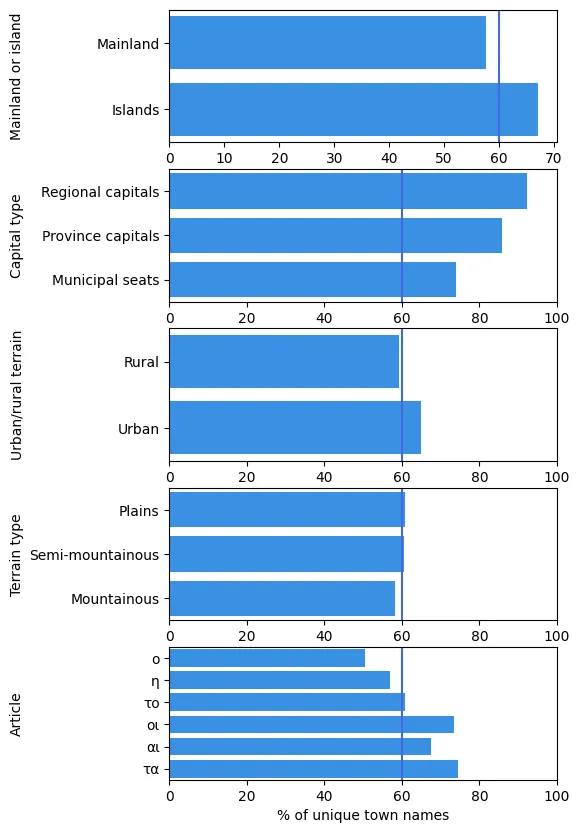

We can also analyze which type of locations tend to have “unique” names, that is, towns that do not share their name with other locations. As a benchmark, bear in mind that 60 % of all Greek locations have unique names.

The number of unique names varies greatly from region to region: while Andros (80,7 %), Kefallonia (79,6 %) and Karpathos (78,8 %) are way above the national 60 %, in the order end of the table we can find Boeothia (45 %), Larisa (45,6 %) and Karditsa (46,8 %).

We can see some clear patterns here: first, islands have a higher proportion of unique toponyms. This is confirmed by the fact that the four island regions (North and South Aegean, Ionian Islands and Crete) are the top four regions by percentage of unique names.

Moreover, capitals and municipal seats tend to have unique toponyms, specially the higher the administrative level is. 12 of the 13 regional capitals (92,3 %), 42 out 49 province capitals (85,7 %) and 241 out of 326 municipal seats (73,9 %). Likewise, plural toponyms and locations in urban areas tend to repeat less. However, there are no significant differences between terrain types and in rural areas.

Regional patterns

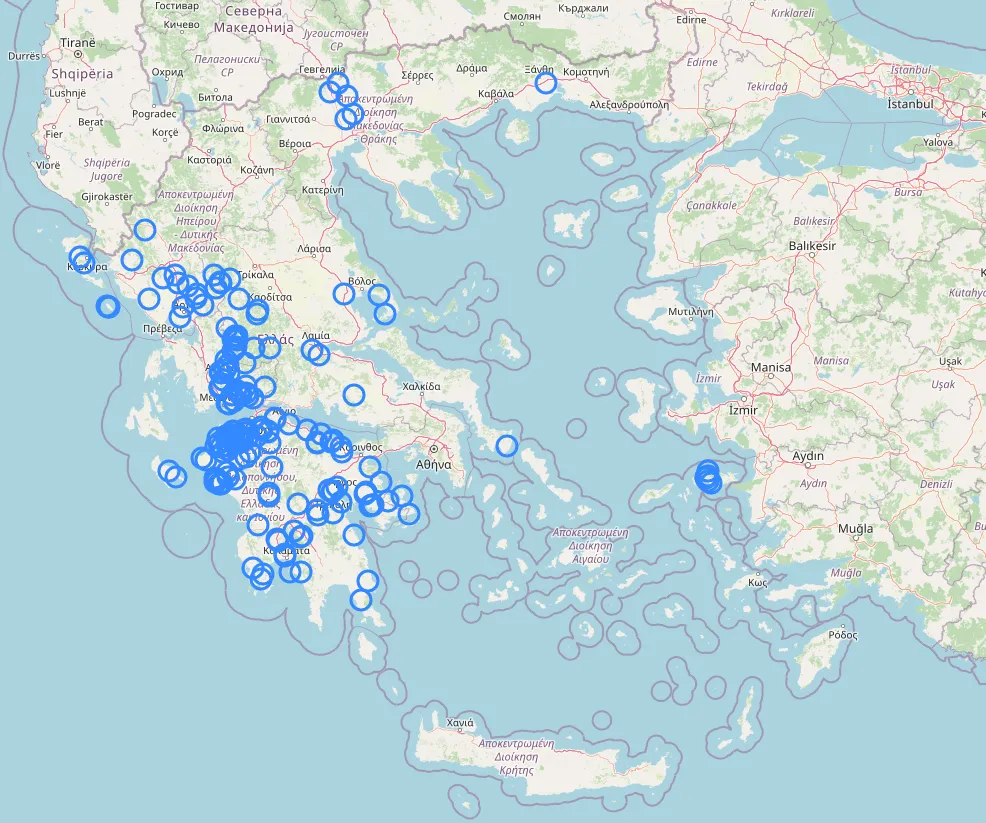

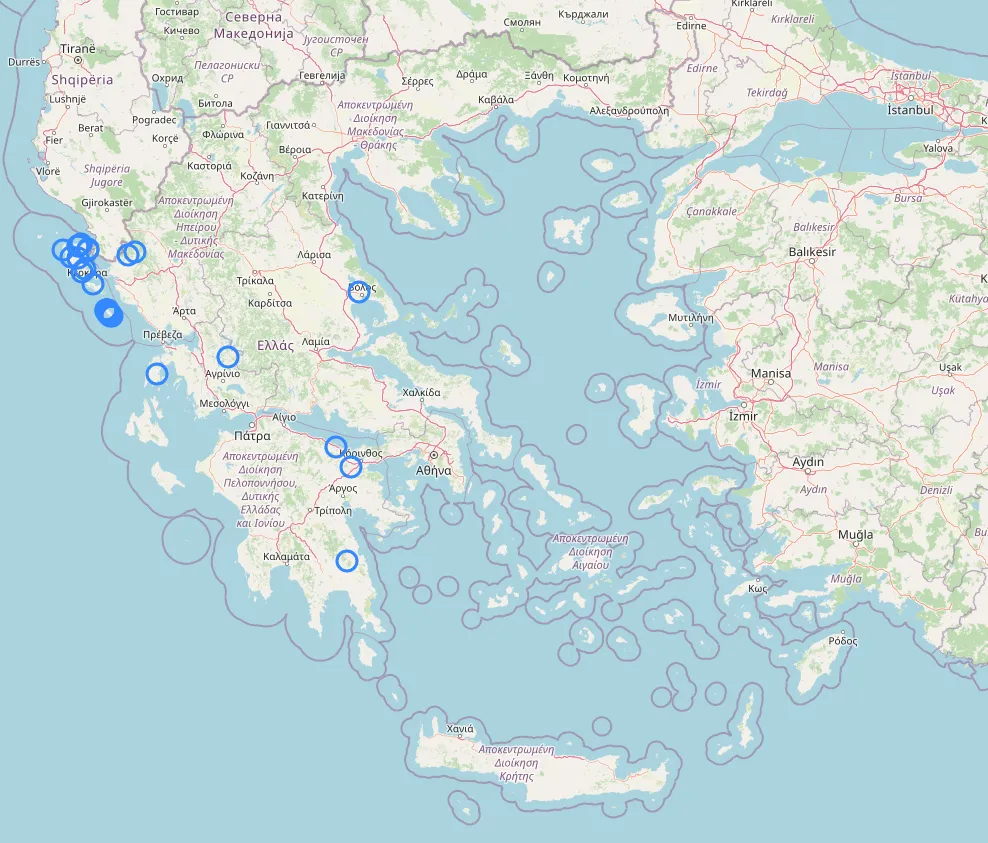

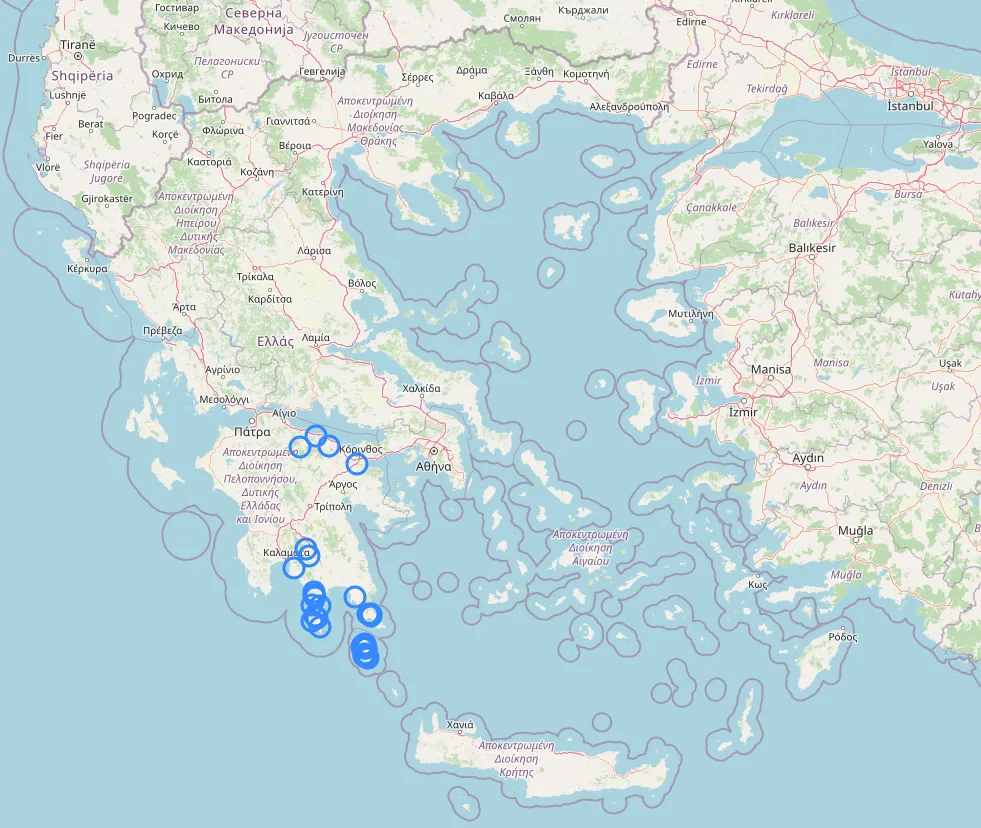

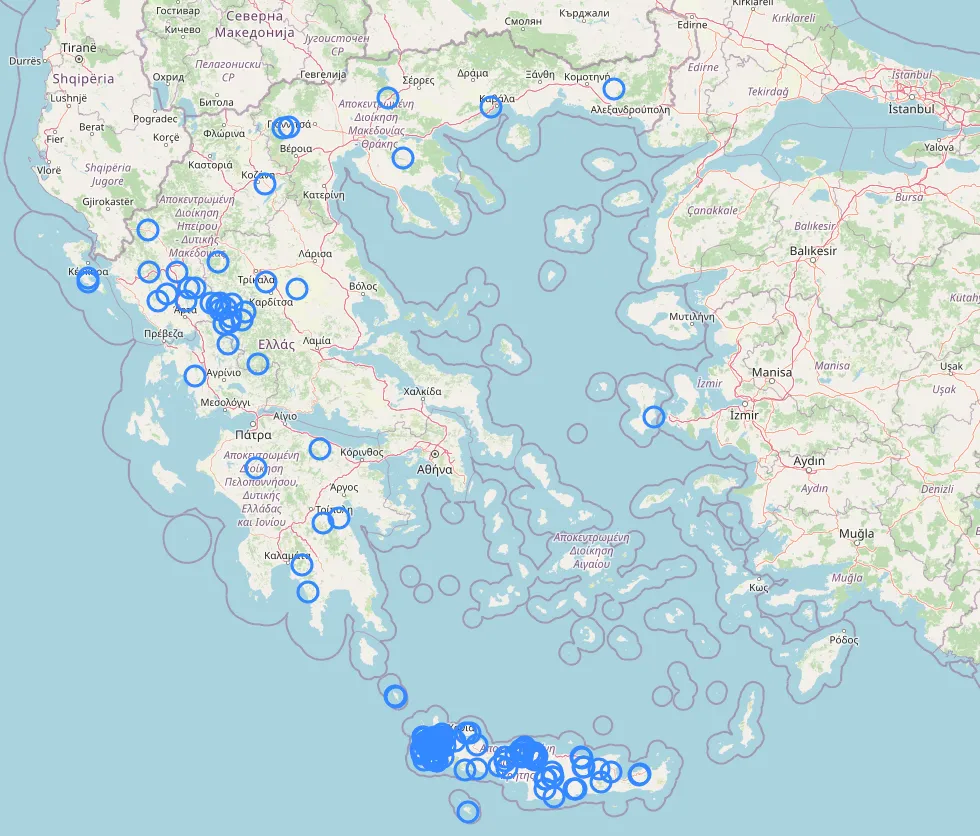

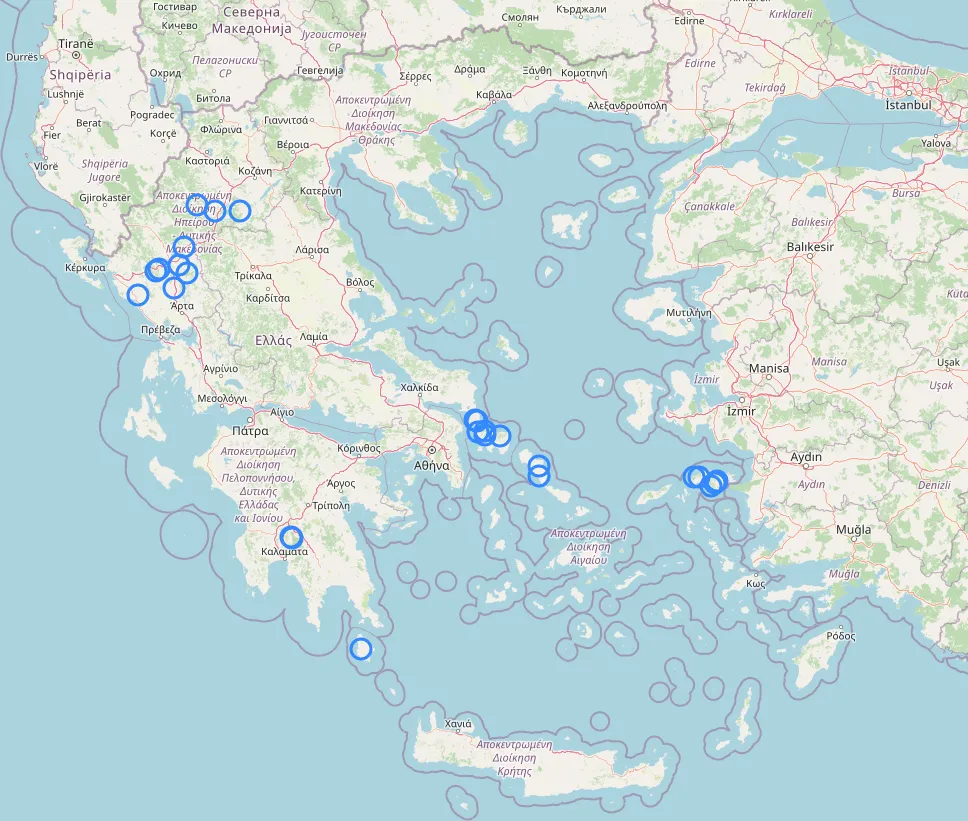

Having a look at Google Maps, it becomes clear quickly that some name endings are more frequent in some places than others. Having a look at the geographic distribution of these endings reveals several interesting stories.

Amongst them, maybe -αίικα (-aíika, read as “-eika”) is the most interesting. It has sparked deep debates on its etymology and the Greek language and orthography due to its unusual combination of vowels. Apparently, this suffix could refer to the place where properties of a family were located, could explain why it is a neuter plural suffix. Its geography is peculiar: it appears mostly in Western Greece mainland, but with several clusters in faraway places like Samos and Kilkis.

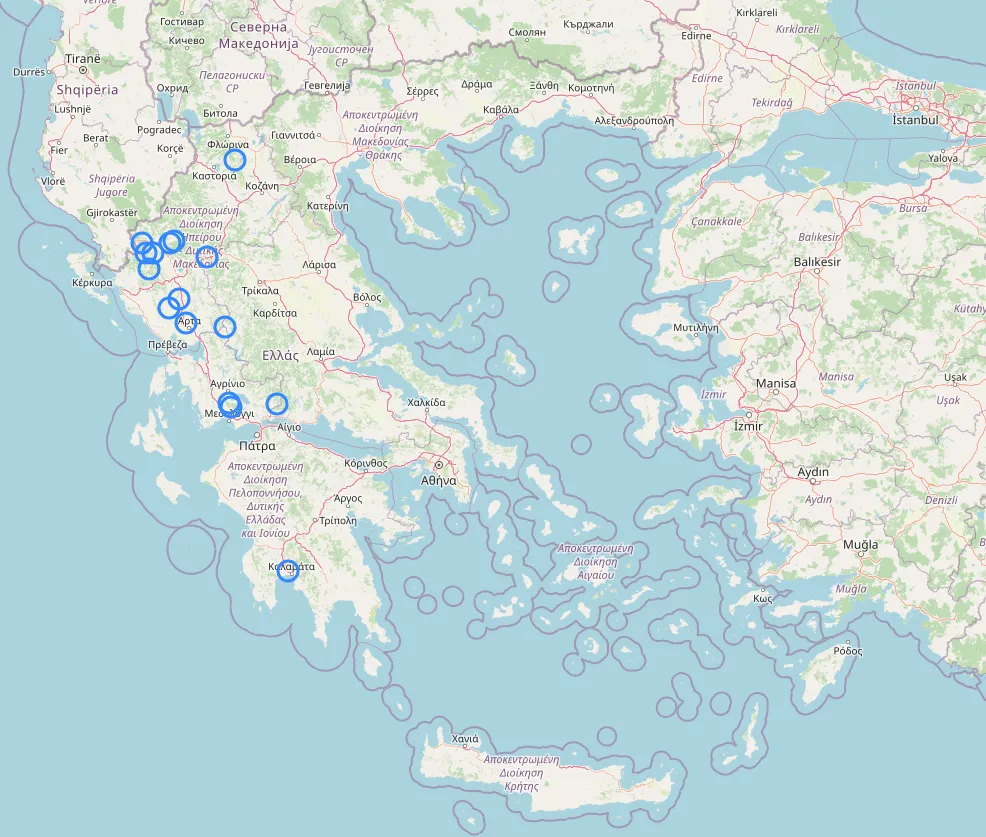

Another interesting topic is the distribution of the suffix -άτα (-áta). Clearly linked to the island of Kefallonia, it is present in almost half of the island’s towns. It is also a neuter plural suffix, which could indicate that it is a local equivalent of -aiíka.

A similar phenomenon can be found with -άτικα (-átika) in Kerkyra, -άνικα (-ánika) in the coast of Lakonia and Kythira, and -ανά (-aná) in Crete and the mountainous area in the center of Greece.

Other interesting patterns are the following:

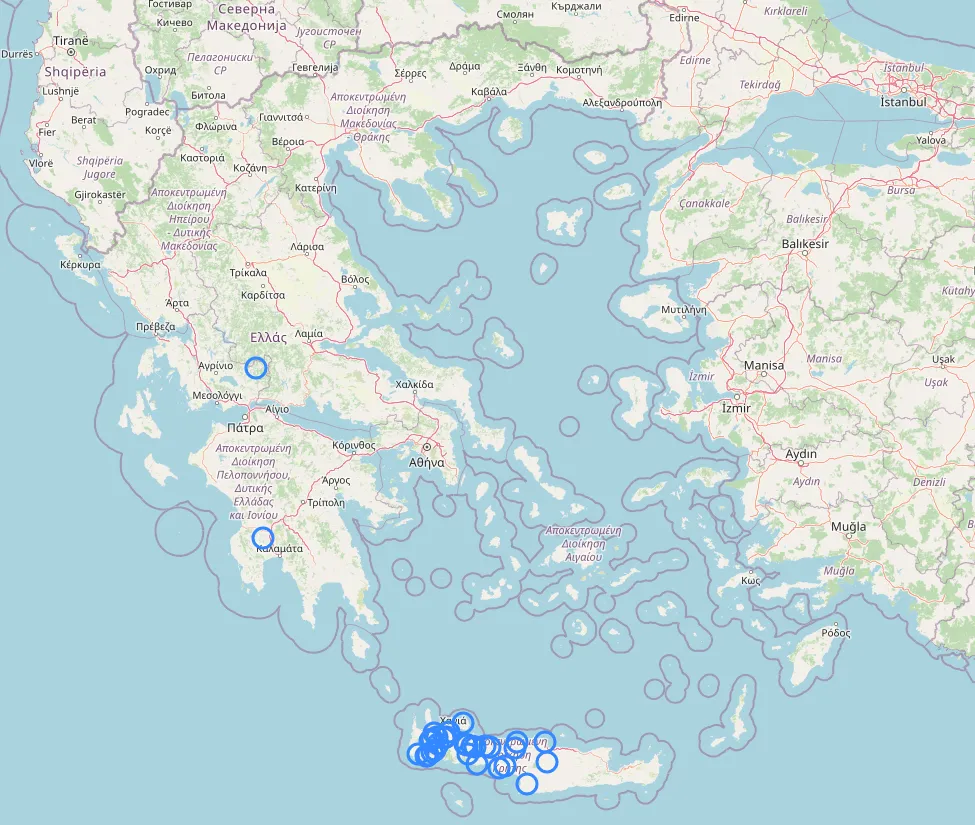

- Masculine singular town names ending in -ές (-és) are located almost exclusively in Western and Central Crete.

- All of the 8 towns ending in -έ (-é), an unusual ending for Greek nouns, are located in Crete. Amongst them, 7 are femenine names (η Μουρνέ, η Κοξαρέ) and form the cluster in the map, while the last one is neuter (το Μαδέ) happens to be the isolated circle in Central Crete.

- Towns ending in-οβο (-ovo) are mostly in the Epirus and have extended mainly along Western Greece.

- Altough the ending in -αίοι (-aíoi, read as -éi) is rare, it tends to appear in clusters and not alone.

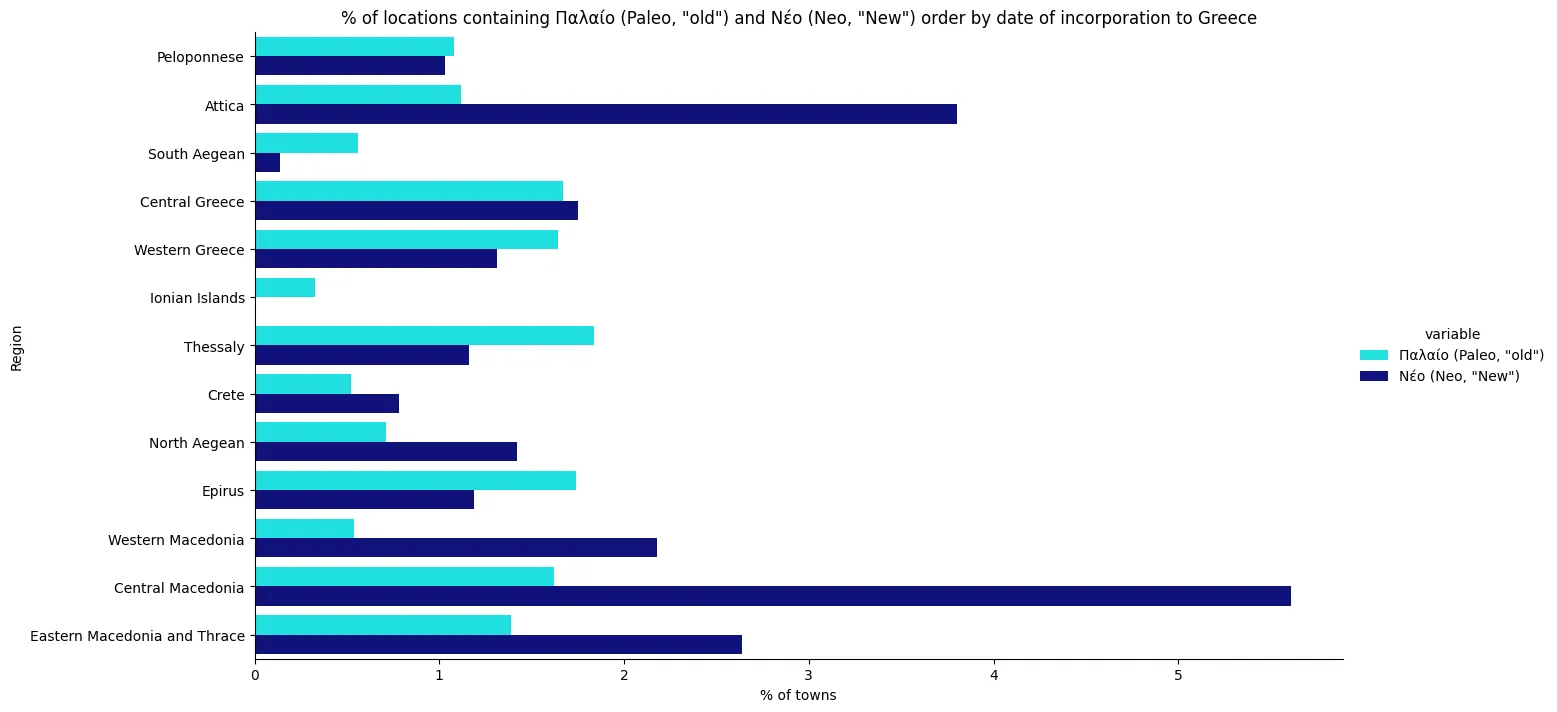

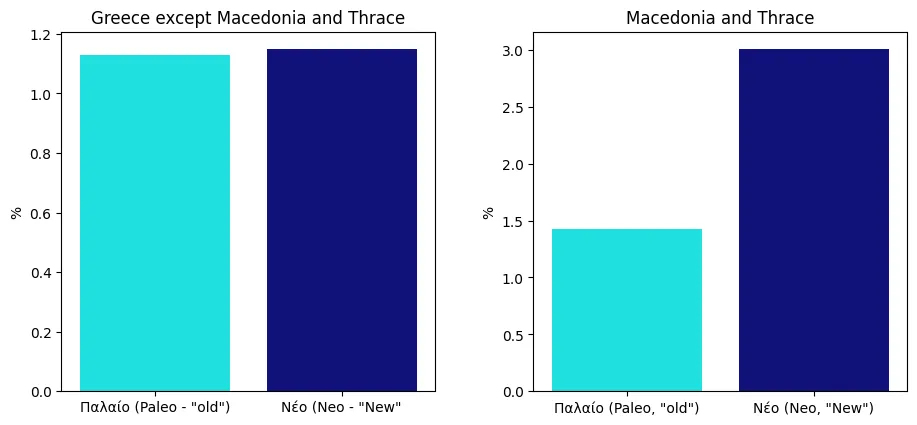

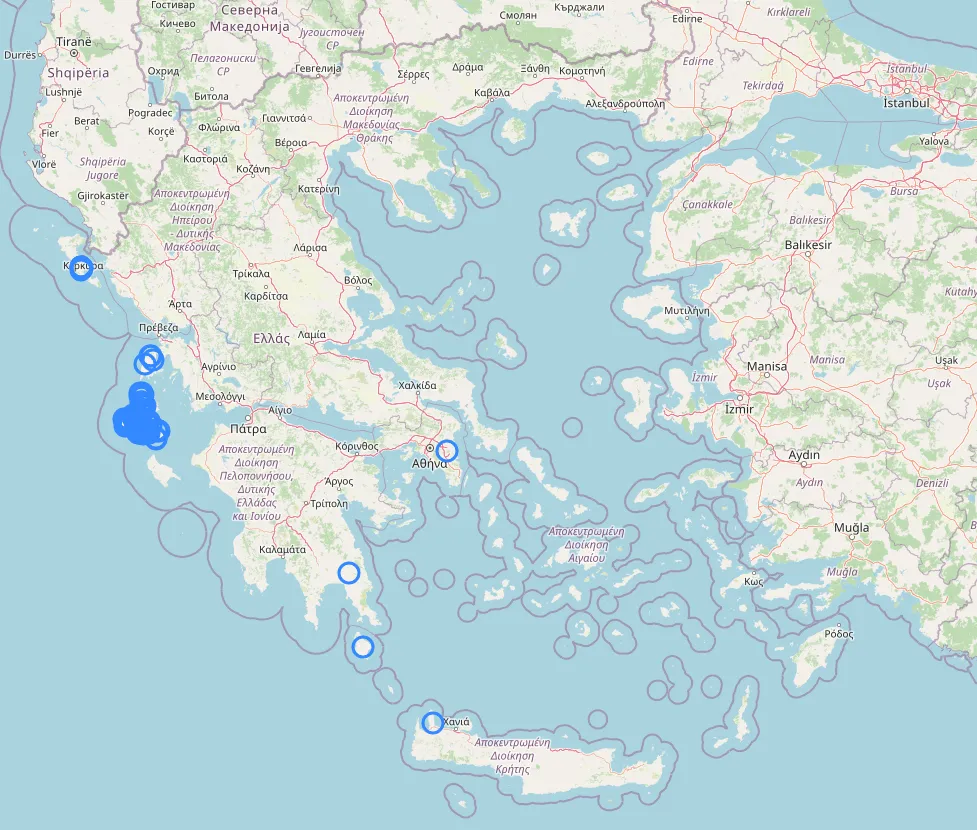

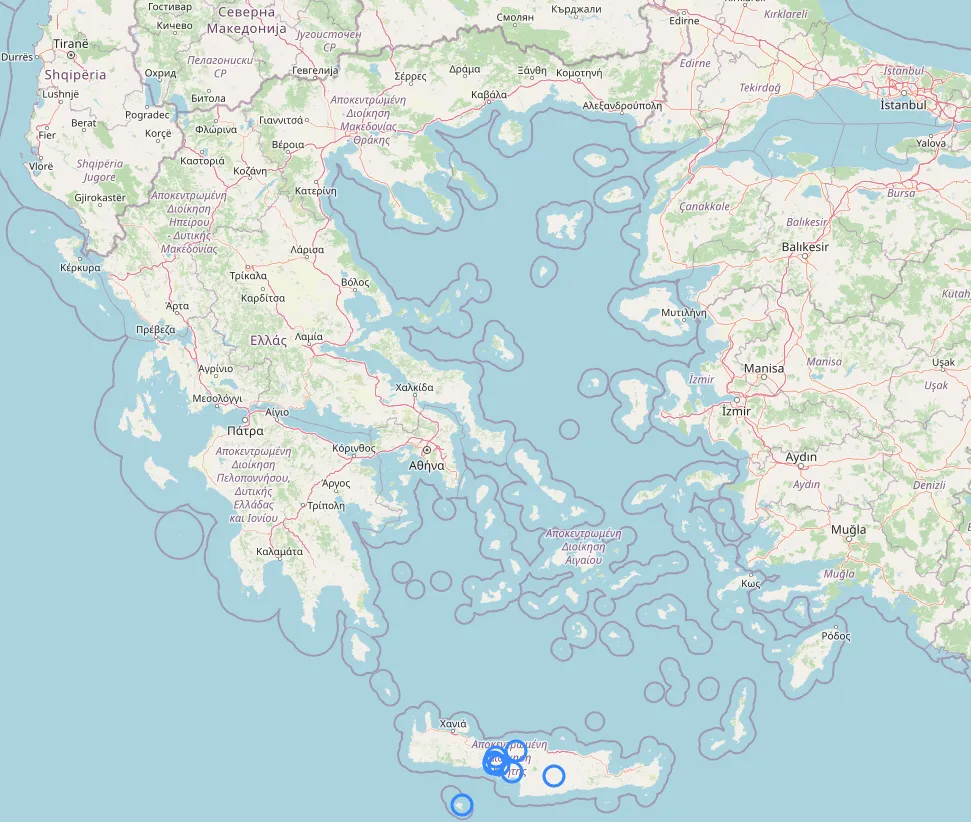

“Old” and “new” towns

Another pattern that is not easily seen through maps is associated with “old” and “new” towns. A significant number of settlements use the terms Παλαίο (Paleo, meaning “old”), Νέο (Neo, meaning “new”) or any of its derivates. It is interesting to see how Macedonia and Thrace, two of the latest territories to integrate into the Greek state after the Balkan Wars, display a higher proportion of “new” towns. This becomes even clearer when comparing the proportion of these territories with the rest of Greece.

Gender and number of Greek toponyms

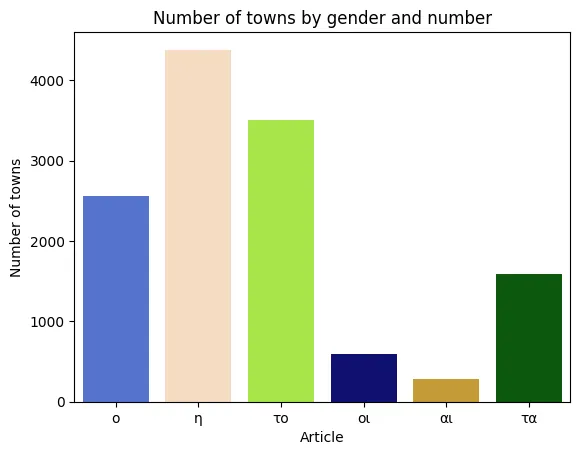

The Greek language has three genders (masculine, femenine and neuter) and two numbers (singular and plural). Every toponym has an article associated with it, which helps us identify the gender and number of each town name. In total, there are six possibilities:

- Masculine articles: singular ο (o), plural οι (oi, read as “i”)

- Femenine articles: singular η (i), plural οι (oi, read as “i” too) in the popular Greek and αι in the conservative Greek (ai, read as “e”), which is used in the database to distiguish femenine and masculine plurals.

- Neuter articles: singular το (to) and plural τα (ta)

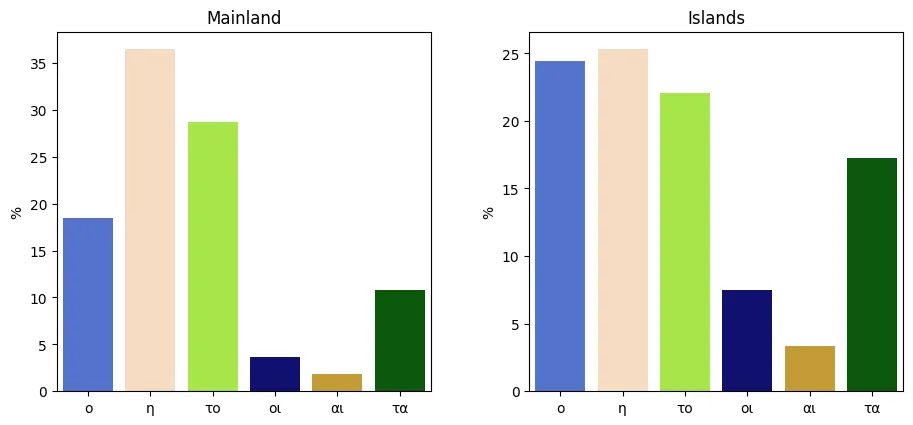

Overall, we see that the femenine singular toponyms are the most frequent, followed by the neuter singular. On the other end, the femenine plural is the rarest of all. Altough singular names are far more frequent, it is interesting to see how neuter plural toponyms are far easier to find. This is mainly due to the plethora of neuter plural suffixes we addressed in the first sections of the article.

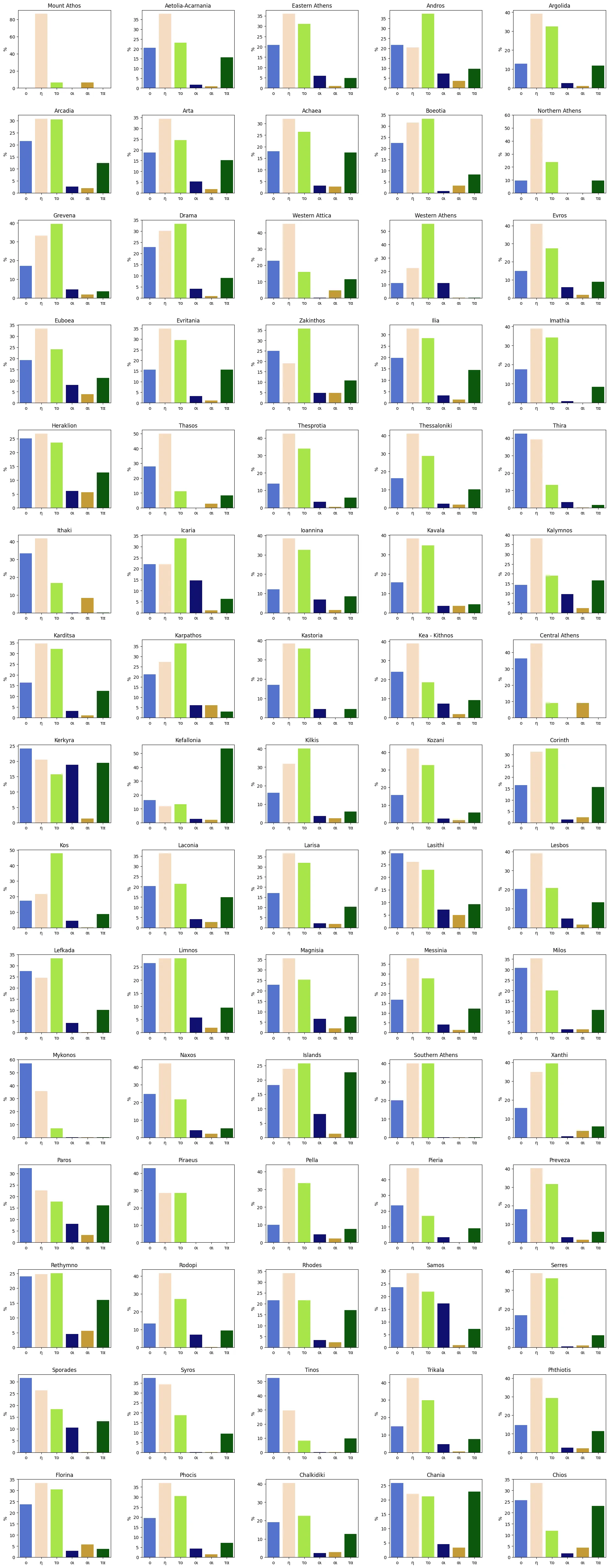

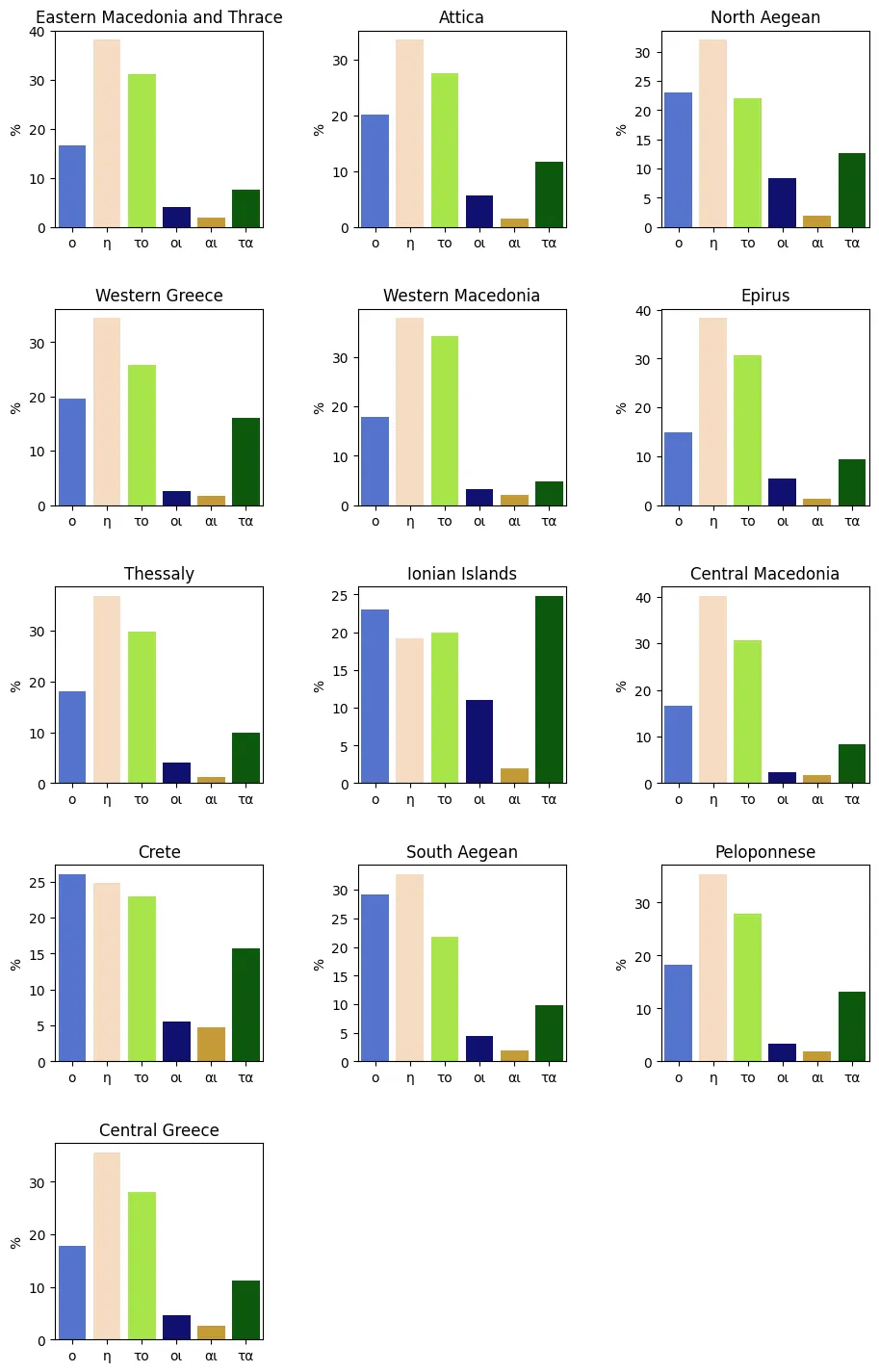

Nevertheless, the distribution of genders and numbers can vary greatly across different regions due to different naming patterns, as shown in the image below.

Taking a closer look at the graphs, we can infer a clear difference between island regions (North and South Aegean, Crete and the Ionian Islands) and the mainland. Islands use femenine singular names far less frequently and favour masculine singular denominations. The case of the Ionian Islands is specially striking: it is the only region in which neuter plural names dominate due to the heavy use of the suffixes -άτα (-áta), -άνικα (- ánika) and, to a lesser extent, -αίικα (-aíika).

These differences can be easily seen by separating the islands and the mainland proportions.

Due to space limitations, you can find the table with the distribution for each province at the end of the article. Some interesting cases are Samos, which has the highest proportion of masculine plural names, Mykonos, that has no plural names, and Kerkyra, with the most balanced distribution.

Other facts

- There are 51 town names containing ϊ and 21 containing ΐ, both unusual characters used in the Greek language.

- The only population containing ϋ in its name is the small town of Ταϋγέτη (Taygeti), near Sparta.

- The town of Παληοχώρα (Paliochora), in Argolis, is the only listed town cointaining -ηο- (-io-) in its name.

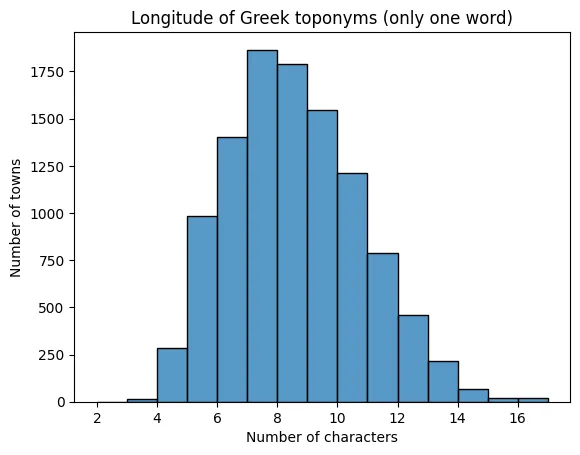

- On average, Greek toponyms are 9 letters long.

- The longest one-word toponym is Σταματογιανναίικα (Stamatogiannaiíka) in Aetolia-Acarnania, with 17 letters.

- The prize to the shortest toponym goes to the island of Ρω (Ro), home of the famous Lady of Ro, who lived alone on the island and raised the Greek flag everyday since 1943 until her death in 1982.

Conclusions

The geogrpahy of Greek toponyms represents the visible part of otherwise abstract aspects, such as history, language and migrations.

Overall, the Pindus Mountains act as a natural barrier between Western Greece, which exhibits more clear patterns in comparison with the rest of the country. The Peloponnese, as one of the most important regions of Ancient Greek civilization, stands out thanks to its variety of town name suffixes and the use of uncommon characters and combinations.

Islands also present interesting features that distiguish them from the mainland: some examples include the higher proportion of unique names, the lower proportion of “old” and “new” town names, the different gender distribution and the use of local suffixes, easy to find in Kerkyra and Kefallonia, but present also in Crete.

As for the rest of the country, few patterns have been spotted aside from Macedonia and Thrace, although more specific research could open new insights for these vast regions. The only common trend along the whole country is the higher probability of important cities and towns of having unique names.

Some future lines of research include further exploring the distribution of other promising startings and endings, like -αινα (-aina, read as -ena), and taking a closer look at the mainland east to the Pindus mountain range and the Eastern Aegean.