Hellas Mellon Project — a forecast of Greece's population

Hellas Mellon Project: a forecast of Greece’s population

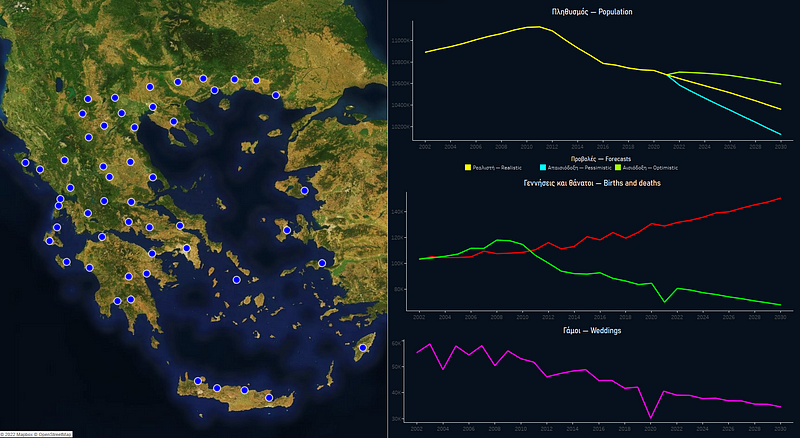

After analyzing the past and present of the population in Greece, studying its future is a natural step. The Hellas Mellon Project was built on this premise, which tries to represent future demographic movements using data science and statistical models.

Explore Greek demographic forecasts on an interactive map through this link.

Why this project?

Despite its small size, Greece is a particular country: in addition to the continental area, it has almost 100 inhabited islands, as well as countless islets. Since I was a child, I have been fascinated by how each island has a unique geography and a particular history, but at the same time can be grouped into archipelagos with common characteristics.

However, some islands appear to be on track to come to an abrupt end due to depopulation. A good example is Antikythera, a small island where the first analog computer in history was found: its population in 2011 did not reach 75 inhabitants. Given this situation, it was logical to ask the following…

How to forecast the future population of Greece?

Firstly, the data were obtained from the Greek Statistical Service (ELSTAT). In particular, files with time series were searched: tables with information about the value of a variable each year, such as the evolution of the population each year. In total, five time series were selected: population, marriages, births, deaths and GDP per capita. Since the information for each town and city is only obtained in the national censuses every ten years, it was necessary to use information grouped at the provincial level, which does offer data year by year for two decades.

To build the predictions, I used an ARIMAX model for each province. This statistical method studies the past behavior of a variable to know its future evolution. Furthermore, it has the advantage that it can be enriched with information on other relevant variables.

The hyperparameters were selected using grid searching (test all combinations to find the most efficient one) and the models were classified based on their RMSE (mean error between the real data and the predictions of that data). Finally, the models were retrained up to three times to correct unrealistic predictions.

Four auxiliary models were calculated: three ARIMA models for marriages, deaths and GDP per capita and one ARIMAX model for births as a function of marriages. The information from these models was added to the population time series to obtain a projection of the demographic evolution of each region until 2030. In addition, two scenarios were built, pessimistic and optimistic, which take into account the inherent variability in the future.

And what are the results?

Overall, very clear trends are observed. The general population of Greece will decrease until it is between 10.1 and 10.6 million inhabitants in 2030. On the other hand, deaths will continue to grow from 130,000 in 2021 to 150,000 in 2030. The opposite occurs with births: will fall year by year to 68,000 new births. A striking fact is the sharp drop in birth rates in 2021, of 17%, probably caused by the COVID-19 health emergency. Exactly the same pattern is repeated with new marriages.

By region, certain patterns are also seen. For example, within mainland Greece, despite the fact that almost all areas are losing population, two types of provinces are distinguished:

- The most populated and urban provinces (Attica, Thessaloniki, Achaia) had more births than deaths until 2012.

- The rest of the provinces, more rural, with a mortality rate above births since the beginning of records in 2002.

This tells us about a general trend towards more advanced depopulation in the interior regions that broke out in large urban centers starting with the economic crisis of 2009 - 2012.

Insular Greece presents a different panorama. In the main archipelagos of the Aegean, depopulation will be suffered less (Cyclades) and population increases are even expected (Dodecanese) with a much higher birth rate than the mainland. Crete replicates the trends of the mainland for its high mortality and low birth rate, but only partially: the island will experience an overall increase in population, probably due to immigration.

A point of interest are the northern Aegean islands: Lesbos, Samos and Chios. In these provinces, the population had been stagnant for 15 years until in 2016, with the crisis of refugees arriving from Turkey, there was a sudden increase of more than 10% until 2020.

Finally, the Ionian islands follow a similar pattern to the provinces of inland Greece, although with exceptions: some examples are Kefalonia, which will maintain its population, and Zante, which exhibited a high birth rate before the crisis.

Conclusions

This project constitutes the extension of the Hellas Database, which explores the recent past of Greek demography. Although similar in substance, the working methods are different: here, it is necessary to incorporate statistical models, which greatly lengthen the information processing time. Fortunately, both data acquisition and visualization were simpler. As lines of improvement, it would have been desirable to have disaggregated data at the locality level and to refine certain models with possible, but risky, forecasts.

All in all, the results have been very interesting: on the one hand, they confirm the depopulation and aging of the Hellenic country that could be intuited from knowledge of social reality. On the other hand, they clash head-on with my previous beliefs about the future of the islands: at the regional level, there are no trends that presage the end of insular Greece. Therefore, and to the joy of the geography lover that I consider myself to be, history will continue to be written in these epic places.